Second World War Shelter

It was 6.50 a.m on Tuesday, 11 June 1940, a day after Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had declared war on Britain and France, that ten Italian war planes took part in the first air-raid on the Maltese Islands. At first, people remained in their homes sheltering under stairways and in cellars, not realising the great damger. Once the houses began to be destroyed and the death toll rising, people sought alternatice places to hide. In the harbour areas, other to spaces within the fortification, people sought refuge in churches, particularly in their sturdy vaulted crypts below. However, even these crypts were not rendering enough safety particularly when the churches’ domes became the targets so not to obstruct enemy dive-bombers.

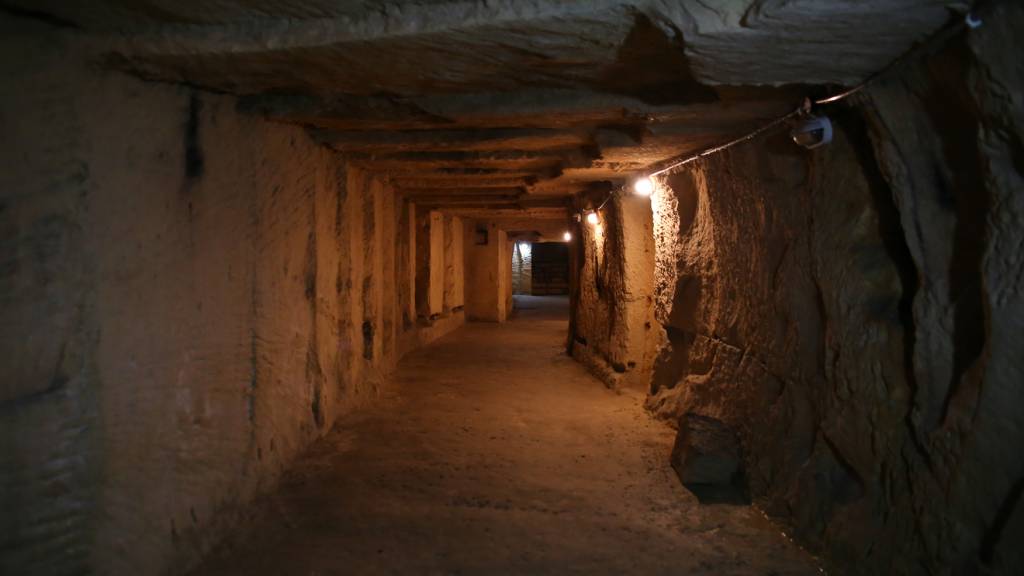

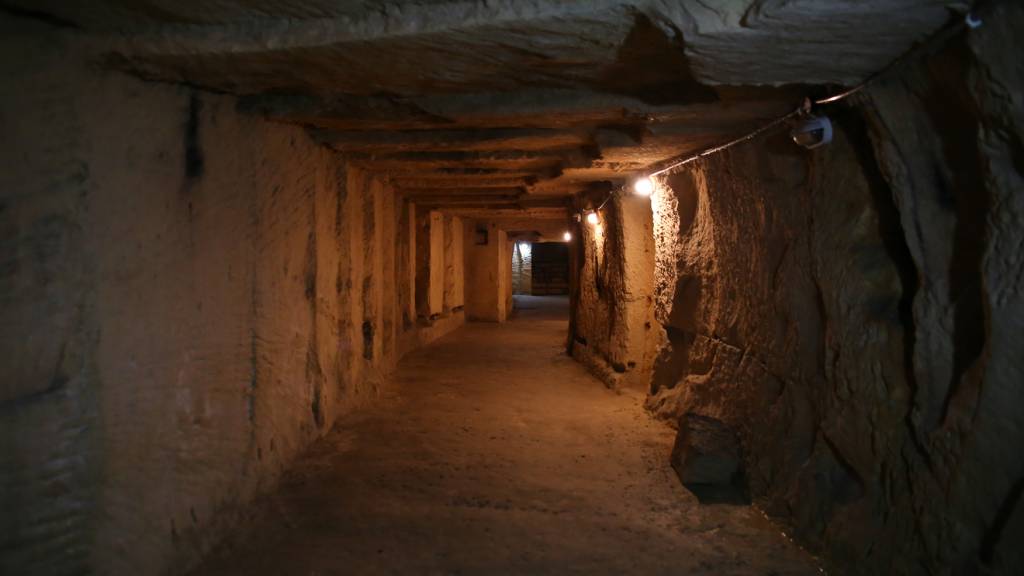

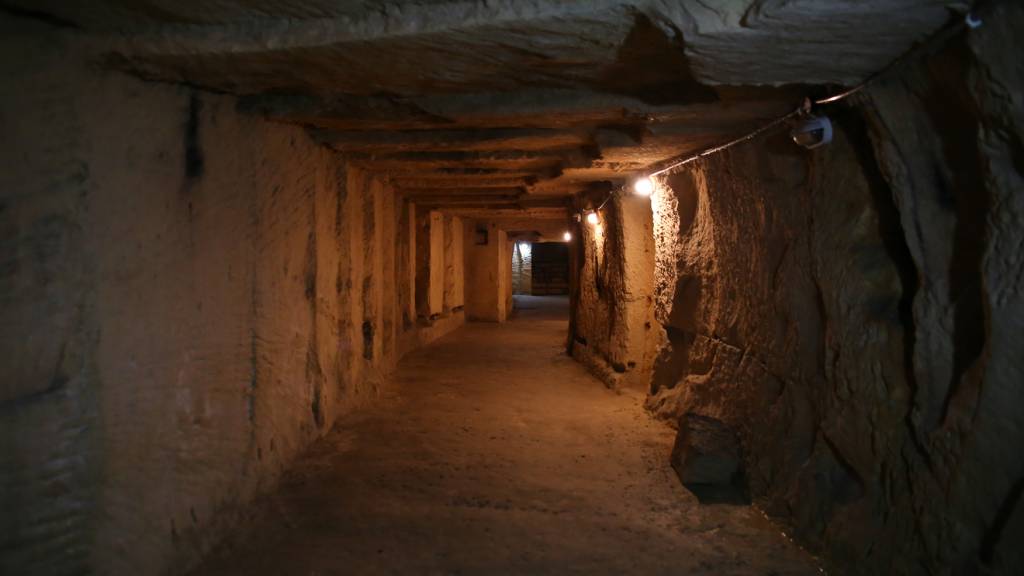

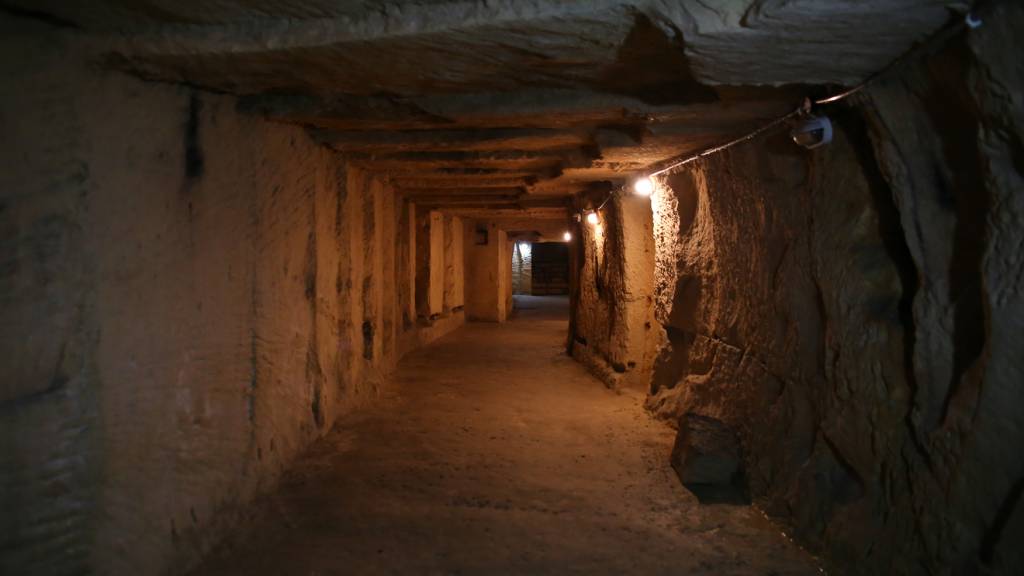

In 1941, the British authorities in Malta approved the excavation of numerous rock-hewn shelters to provide refuge for the populace during aerial attacks. The massive fortifications around the Grand Harbour area were ideal places to excavate into. Numerous others were excavated under towns and villages and had entrances and exits at street level accessed by means of winding steps. Air-raid shelters usually consist of a main gallery which may also contain several rock-hewn rooms. Some shelters are a labyrinth of hundreds of metres in length, while others were dug privately under houses or in gardens, usually using an old well as an entrance shaft. Or beneath a basement, and mostly consisting of just a couple of rooms, enough to store some valuable belongings and food, yet offering safe cover for members of the household during an air-raid. All shelters had at least two entrances or exits, but many of the communal ones had more according to the capacity of the shelter.

The shelter beneath the Augustinian church and friary was excavated early in 1941 and practically runs along and parallel with the façade on Old Bakery Street (Triq l-Ifran). It consists of a main gallery, which was later enlarged and has four cubicles or rooms, in which entire families had lived. One was even used as a chapel. The two public entrances were situated in Old Bakery Street and in St. John’s Street (Triq San Ġwann), with two others accessible from the church’s crypt. One stairway linked to the shelter via an old well, while another was through a ventilation shaft which was later converted into a spiral staircase.

The walls of the gallery contain some unique features, particularly the progress of excavations and the later widening, in the form of stepped rock excavation. In those days, labourers were paid by the yard (91,44cm) and these ‘steped excavations’ are close to this measurement. Also unique are a good number of graffiti, some crudely chiselled in the rock, while others are in pencil and portray life during those turbulent years; aeroplanes in combat, faces, names, dates and even a bad representation of Hitler. Unfortunately, one must have a good eye for them as the years and humidity have taken their toll. One particular graffito commemorates a death, possibly that of a baby.